- Nutrition

- Posts

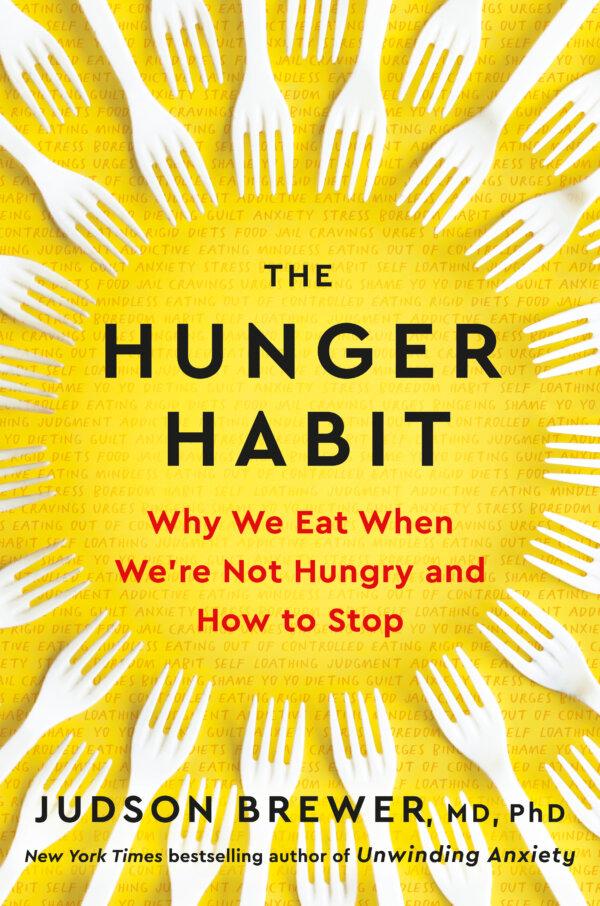

- How to Break the Hunger Habit

How to Break the Hunger Habit

You can train your brain to resist the lure of tempting foods, Judson Brewer says . in his new book, ‘The Hunger Habit.’

(Stock-Asso/Shutterstock)

Do you have a complicated relationship with food? If so, you’re not alone, according to Dr. Judson Brewer’s new book, “The Hunger Habit: Why We Eat When We’re Not Hungry and How to Stop.” Dr. Brewer, an addiction psychiatrist and neuroscientist, has seen “as many different ways to have a bad relationship with food” as he has patients.

Dr. Brewer wrote “The Hunger Habit” to address why we form bad eating habits and to challenge readers to break them using a 21-day plan.

If we can understand what’s going on in our brains when we “can’t stop eating,” we can stop feeling guilty and frustrated about our inability to stick to a conventional diet plan, he says.

Dr. Brewer is an expert in the very human tendency to get stuck in ruts—and the anxiety that this tendency causes. His earlier book “Unwinding Anxiety” tackles the habits that lead to anxiety and maps out a three-step plan to retrain anxious brains.

“The Hunger Habit” zeroes in on “habit loops” that can keep us trapped in what he calls “food jail,” unable to break free from overeating.

How Food Habits Form

“We form all sorts of associations with food by learning to eat for celebration, connecting with others, consoling ourselves when we are sad, or simply eating as something to do when we’re bored,” Dr. Brewer told The Epoch Times.

The sheer abundance of food in modern society contributes to the problem.

“If food isn’t around, we can’t make these associations,” Dr. Brewer pointed out. More importantly, processed food is “engineered to be addictive,” he said.

Some studies suggest that ultra-processed foods, with their engineered combination of carbohydrates and fats, may be as addictive as cigarettes and alcohol. The addictive quality of unhealthy food, along with its ability to affect our moods, combine to complicate our relationship with food, Dr. Brewer said.

It’s very difficult to eat the way we know we “should,” he told The Epoch Times, because “our thinking brain is not nearly as strong as our feeling body. An urge to eat is much stronger than [the thought that] we shouldn’t.”

That’s why traditional diets that focus on restricting calories are ineffective for so many of us. Our habits will invariably overtake our willpower, says Dr. Brewer. He lists four reasons not to rely on willpower:

What you can’t have, you want more of.

What you resist persists.

Failure leads to backsliding.

Willpower isn’t part of habit change strategies.

Habit Loops

Rather than relying on willpower, Dr. Brewer suggests in his book that a better strategy for breaking bad habits is to be aware of the loops that keep us repeating unhealthy behavior. He defines the elements of a habit loop as:

Trigger/cue

Behavior

Result/reward

These three elements train our brain through positive reinforcement, Dr. Brewer writes. He uses the example of a baby who delights in tasting ice cream for the first time: “Trigger: See ice cream. Behavior: Eat ice cream. Result: Yum! Repeat.”

When we face anxiety or emotional turmoil, we learn through negative reinforcement—using the same trigger/behavior/result sequence—that eating the ice cream will help us avoid “wallowing in our emotions.” In short, negative reinforcement “crosses the food wires” with the mood wires in our brains, Dr. Brewer writes.

“If you feel bad, your brain can step in and remind you that eating feels good, or at least blanks out the bad feelings—temporarily,” he writes.

The 21-Day Challenge

Dr. Brewer challenges readers, once they have identified eating habit patterns, to “interrupt” them using awareness—“not willpower”—then to “leverage the power of the brain to step out of old and into new habits that nurture us mentally and physically.” He invites us to embark on a 21-day challenge to reset our relationships with food.

Dr. Jud Brewer (Mahri Leonard-Fleckman)

“The 21-day program is based on years of research and clinical experience,” Dr. Brewer told The Epoch Times. “I’ve had several people report that they’ve lost more than 100 pounds and importantly, have kept that weight off for more than five years.” One person said it was the easiest weight loss plan he’d ever tried.

Part one of the challenge (days one through five) involves setting a “baseline” by exploring your relationship to food and eating throughout your life. The next steps are to map your food habit loops and determine the situations that prompt you to eat because of emotion and habit rather than hunger.

Part two (days six through 16) is all about interrupting those habit loops through eating mindfully, being attentive, getting to know “pleasure plateaus,” and controlling cravings. Dr. Brewer recommends “RAINING” on the “craving monster” using a tool called RAIN, based on a practice developed by American meditation teacher Michele McDonald. RAIN steps include:

Recognizing a craving is coming on and relaxing into it

Allowing and accepting the “wave” of the crave

Investigating or studying the craving

Noting the physical experience craving causes

“Riding out” a craving this way has been proven to help people beat the craving monster, and not just in the case of food cravings, Dr. Brewer notes. He discusses this in more detail in his 2018 book “The Craving Mind: From Cigarettes to Smartphones to Love—Why We Get Hooked and How We Can Break Bad Habits.”

‘End the War, Begin the Peace’

Part three (days 17 through 21) helps readers identify new, healthy habits relating to food—what Dr. Brewer calls “finding the bigger better offer” (BBO). Avoiding overeating comes to feel like a BBO when it feels better than eating too much, he writes, and when a healthy habit is seen as a BBO, we choose it voluntarily.

We have the power to become “disenchanted” with unhealthy foods’ effects on our bodies and “enchanted” with beneficial foods, readers learn in part three of the challenge. An “enchantment databank” of foods that are healthy and satisfying is an important tool to develop at this point in the process, Dr. Brewer writes.

Near the end of the challenge, Dr. Brewer reminds us to be kind to ourselves and to be aware that past trauma may cause us to judge ourselves harshly.

“We are so accustomed to beating ourselves up for our unhelpful habits, we make a habit of that, too,” he writes. In short, self-kindness is a BBO rather than self-judgment, and it can make a big difference as we seek to change our lives and habits.

Eating can be an “act of mindful self-care and pleasure” when we kick the hunger habit and break free from unhealthy eating patterns.